Why agentic architectures fail economically and how hybrid SLMs change the cost curve

The most expensive part of an LLM system is not inference.

In production environments, the dominant cost of large language model systems is rarely the price of tokens. Instead, it is the human time spent designing, monitoring, debugging, and explaining systems whose behavior becomes increasingly opaque as complexity grows.

Over the past year, agentic architectures (often built on top of Retrieval-Augmented Generation) have been proposed as a way to improve reasoning, autonomy, and task completion. In controlled demos, these systems can appear remarkably powerful. In production, however, their operational cost profile is frequently underestimated.

Each additional reasoning step introduces not only more inference calls, but also a wider surface for failure, higher latency, and a growing need for human intervention. This creates a fundamental mismatch: reasoning capability scales faster than operational controllability.

In this article, I examine this mismatch through a concrete experiment comparing a fully agentic RAG pipeline with a hybrid architecture based on fine-tuned Small Language Models (SLMs) and lightweight routing. Rather than optimizing for benchmark performance, the focus is on how different design choices affect cost curves, debuggability, and incident response in production-like settings.

The key insight is not that smaller models are “cheaper”. It is that specialization changes the economics of reasoning systems, shifting cost away from unbounded inference and back toward predictable, controllable components.

The hidden cost of reasoning systems.

The primary cost driver of modern LLM systems is not model size, context length, or token pricing. It is the cost of control.

As reasoning pipelines become more complex (adding planners, tools, memory layers, and retries) the system's behavior becomes harder to predict and harder to explain. Each additional component introduces new failure modes, longer execution paths, and more opportunities for silent degradation. The result is not just higher inference cost, but a growing burden on the humans responsible for keeping the system reliable.

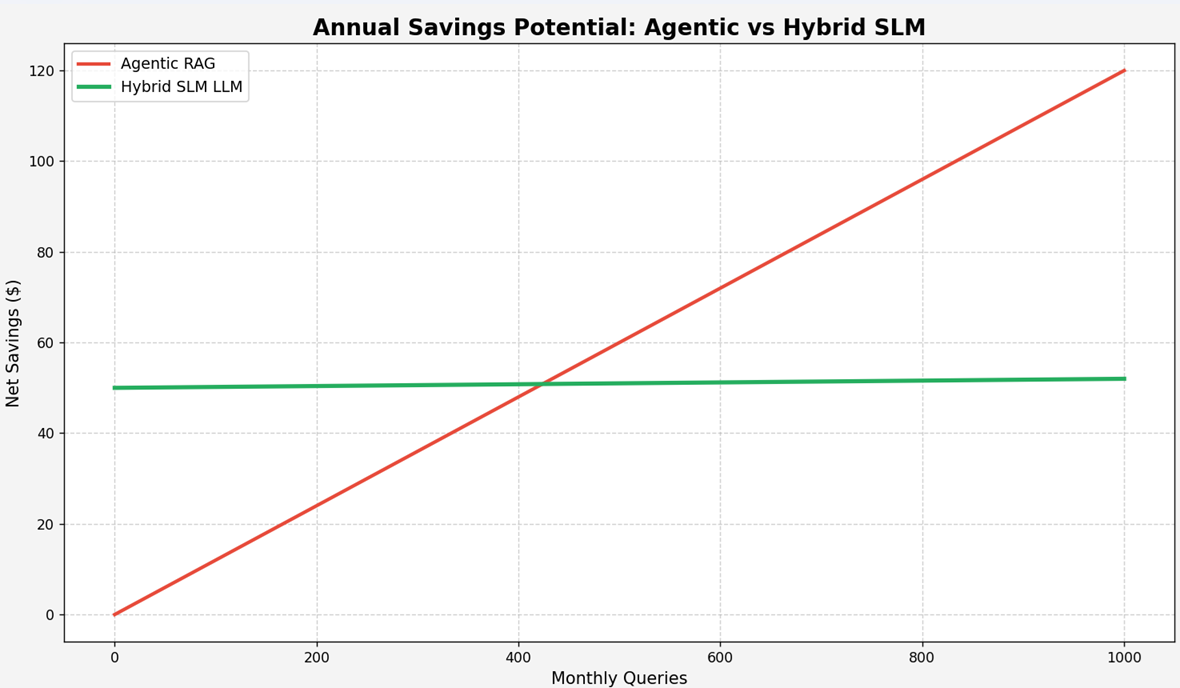

The figure below illustrates this effect. While inference-heavy architectures such as agentic RAG scale linearly in terms of token usage, their total operational cost grows superlinearly once human intervention is taken into account. Debugging multi-step reasoning chains, inspecting partial traces, and performing root cause analysis after incidents quickly dominate the cost profile.

What is often missed in architectural discussions is that time does not scale like compute.

A failed request that triggers multiple retries, partial tool executions, or inconsistent intermediate states can consume hours of engineering effort, even if the direct inference cost remains low. As system load increases, these rare failures stop being rare.

This is why many agentic systems appear economical in early prototypes but become increasingly expensive in production. Their cost curves are shaped less by tokens and more by operational entropy: the accumulation of complexity that erodes observability, predictability, and control.

Understanding this hidden cost is essential before comparing architectures. Without accounting for the human effort required to operate and debug reasoning systems, any cost analysis remains incomplete.

Why Agentig RAG scales poorly

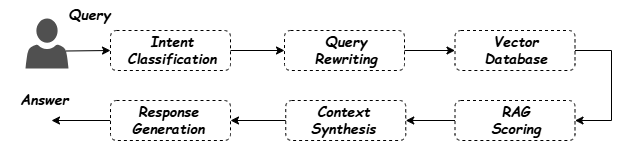

To understand why agentic architectures scale poorly in production, it is useful to examine a single query traced end-to-end through an agentic RAG pipeline.

The experiment analyzed here consists of a factual query executed against an agentic RAG system with intent detection, query rewriting, multi-stage retrieval, external source validation, synthesis, and post-hoc quality checks. While each component is individually reasonable, their composition reveals a different picture.

For a single user query, the system executed 12 LLM calls, resulting in:

- ~ 5700 input tokens

- ~ 2000 output tokens

- 0.12$ in inference cost

At first glance, these numbers may appear acceptable. The response quality score was high, and the final answer was grounded in authoritative sources. However, these metrics obscure the structural problem.

Each LLM call represents a branching point in the execution graph. Intent classification, query rewriting, retrieval scoring, synthesis, validation, and hallucination checks all introduce states that must be coordinated, logged, and interpreted when something goes wrong. When a failure occurs, the question is no longer "did the model answer correctly?" but "which step failed, and why?"

The trace makes this explicit. A single request produces multiple intermediate artifacts (rewritten queries, ranked document chunks, synthesized contexts, validation reports) each with its own assumptions and potential inconsistencies. While this structure improves answer quality in isolation, it significantly increases the debug surface area of the system.

More importantly, these costs scale with reasoning depth, not with request volume. As traffic increases, even low-probability failures accumulate, and human intervention becomes unavoidable. Root cause analysis in such systems often requires reconstructing execution paths across multiple model calls, external dependencies, and heuristic thresholds.

This is the core scaling failure of agentic RAG: reasoning steps multiply faster than observability and control mechanisms.

In practice, this means that adding more reasoning to improve quality can paradoxically reduce system reliability and increase operational cost. The system does not fail catastrophically; it fails expensively, by demanding increasing amounts of expert attention to maintain acceptable behavior.

Specialization changes the cost curve

The failure mode of agentic RAG systems is often framed as an implementation problem: better prompts, better tools, better orchestration. In practice, the issue is more fundamental. These systems assume that general-purpose reasoning can be applied uniformly across all tasks without significantly affecting operational cost.

Specialization breaks this assumption.

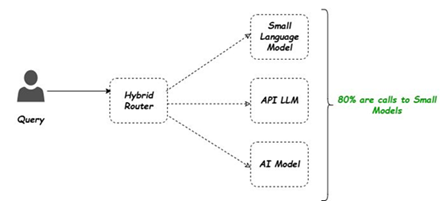

By delegating well-scoped, high-frequency tasks to fine-tuned Small Language Models (SLMs), it becomes possible to decouple reasoning depth from system complexity. Instead of invoking a large model for every decision, a lightweight routing layer determines whether a request can be handled by a specialized model or requires escalation to a general-purpose LLM.

The impact of this shift is not limited to inference cost. Routing introduces a control surface: a deliberate point at which behavior can be inspected, constrained, and reasoned about. In a hybrid architecture, most requests follow short, predictable execution paths. Only a minority traverse deeper reasoning chains.

This changes the cost curve in two important ways. First, the average number of LLM calls per request drops sharply, reducing both latency and exposure to cascading failures. Second, failures become easier to localize. When a specialized model produces an incorrect response, the error surface is smaller, and root cause analysis does not require reconstructing multi-step reasoning graphs.

Crucially, this approach does not aim to replace large models. Instead, it repositions them as exceptions, not defaults. General-purpose reasoning is reserved for genuinely ambiguous or novel queries, while specialized models handle the stable core of the workload.

From an operational perspective, this leads to a qualitatively different system behavior. Cost grows more predictably with load, incident analysis becomes tractable, and human intervention shifts from continuous supervision to targeted escalation.

Specialization, in this context, is not an optimization. It is a structural change that restores controllability to reasoning systems.

A hybrid experiment

To evaluate the impact of specialization on system behavior, I implemented a hybrid architecture combining a fine-tuned Small Language Model (SLM) with a general-purpose LLM, connected through a lightweight routing layer.

The goal was not to optimize for absolute answer quality, but to observe how different architectural choices affect cost, latency, and operational complexity under realistic usage patterns.

The SLM was fine-tuned on a narrow, domain-specific corpus and deployed locally. Queries falling within this domain were handled entirely by the specialized model, while broader or ambiguous requests were routed to a remote LLM. Both paths were instrumented to collect execution traces, latency, token usage, and failure signals.

Compared to the fully agentic RAG pipeline described earlier, the hybrid system exhibited a markedly different execution profile. Most queries completed in a single model call, with no intermediate reasoning steps or post-hoc validation. As a result, average latency dropped significantly, and inference costs remained stable as load increased.

More importantly, the operational characteristics changed. Failures were easier to isolate, and debugging typically involved inspecting a single model response rather than reconstructing a multi-stage reasoning graph. In practice, this reduced the time required for root cause analysis and eliminated entire classes of cascading errors observed in the agentic setup.

It is worth emphasizing what this experiment does not claim. The hybrid approach does not outperform agentic RAG in all scenarios, nor does it eliminate the need for large models. Instead, it demonstrates that introducing specialization and routing can fundamentally alter the cost structure of reasoning systems, trading maximal flexibility for predictability and control.

The experiment suggests that, for many production workloads, this trade-off is not only acceptable but desirable.

What this means for production teams

For production teams, the primary challenge of LLM systems is not model capability but operational sustainability. Architectures that maximize reasoning flexibility often do so at the expense of predictability, making them difficult to operate with limited time, budget, and expertise.

The results above suggest a different framing. Instead of asking "how much reasoning can we add?", teams should ask "how much reasoning can we afford to control?"

Hybrid architectures shift this balance. By handling the majority of requests through specialized, bounded models, teams can reduce the cognitive load required to operate the system. Monitoring becomes simpler, incident response faster, and failure modes more legible. This is particularly relevant for small and medium-sized teams, where a single production incident can consume days of engineering time.

From a cost perspective, the benefits extend beyond reduced token usage. Fewer model calls mean fewer logs to inspect, fewer thresholds to tune, and fewer opaque interactions between components. Over time, this translates into lower maintenance cost and less dependence on a small number of domain experts who "understand how the system really works."

Perhaps most importantly, specialization enables intentional escalation. When a request is routed to a large model, it is a conscious decision rather than an implicit default. This makes reasoning expensive by design, encouraging teams to reserve it for cases where its value is clear.

In practice, this approach supports a more mature production posture. Systems evolve incrementally, failures are contained, and improvements can be measured against operational metrics rather than benchmark scores alone.

For teams deploying LLMs in real environments, the question is not whether agentic systems are powerful. It is whether their power aligns with the team's capacity to operate them.

Limits and failure modes

The hybrid approach described in this article is not a universal solution. Its advantages depend on task stability, domain boundaries, and the availability of meaningful supervision signals. In environments where queries are highly diverse or poorly defined, specialization may introduce brittleness rather than control.

Fine-tuned SLMs are also sensitive to distribution shifts. When the input space drifts beyond the training domain, failures can be subtle and harder to detect than in general-purpose models. Without explicit routing confidence thresholds or fallback mechanisms, incorrect specialization can degrade system performance silently.

There are also organizational limits. Designing and maintaining specialized models requires upfront effort: data curation, evaluation, and periodic retraining. Teams without the capacity to invest in these activities may find that the promised operational gains do not materialize.

Finally, hybrid systems do not eliminate complexity—they redistribute it. While reasoning depth is reduced at runtime, architectural decisions move earlier in the lifecycle. This shifts effort from reactive debugging to proactive design, which may not align with all team cultures or incentives.

These limitations are not arguments against specialization, but reminders that architectural choices encode trade-offs. The goal is not to minimize reasoning, but to make its cost visible, bounded, and intentional.

In that sense, hybrid architectures do not simplify LLM systems. They make them operable.

Limits and failure modes

Routing behavior and response quality were evaluated using a combination of manual task-specific assessment and automated checks. The focus was on correctness and operational behavior rather than benchmark optimization.